Moved Permanently

The document has moved here.

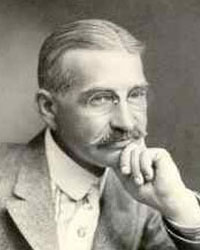

One of the first to pilot the concept of 20th century multi-media performance art was that most American of American fantasists, Lyman Frank Baum. Baum had a lot in common with his creation, the humbug Wizard of Oz – his early years were spent on the road as an actor, traveling china salesman, and purveyor of dry goods at a shopping bazaar in South Dakota. But when a chronic heart condition put an end to his life as a traveler, he settled down to writing the fantasies that have convinced generations of readers that the Land of Oz was a great deal more real than the homework waiting to be done or the messy rooms soon to be receiving parental inspection. Not only was he the inventor of an astonishing, original, and arguably feminist fairyland, discovered by a little girl from Kansas and ultimately restored to the rule of Ozma, the-girl-who-was-once-a-boy – but the array of works deriving from his original series – from the 1939 Wizard of Oz to The Wiz to the book and musical Wicked, to name just a few, would probably all have delighted him. He was a proud adapter of his own work, and not above trying to squeeze every penny possible out of the musicals, early silent movies, and stage performances based on his books.

At least partly out of this desire, perhaps, rose his early creation of the Fairy-Logue and Radio Plays, "a two hour mixed-media show that dramatized his fairy stories by means of narration by himself, enactment by live actors, slides, and short films." (This quotation, and much of the information that follows, come from Katharine M. Rogers' excellent biography, Creator of Oz, published in 2002 by St. Martins.) A showman to his core, Baum would dress all in white, introduce his show by describing his encounter with a fairy who invited him to be Royal Historian of Oz. He would then step off stage, only to re-appear in the same white suit in a series of films and slides in which he would lead characters out of the pages of his books to re-enact their stories. Very unusually for the time, the films and slides were often in color, having been sent off to Paris for hand-tinting (then called a radio process, hence "radio plays" – this was still before radio was being pioneered). A 27-piece orchestra played behind the silent film and Baum's off-stage narration, and live characters interacted on stage with the stories. This was a far cry from silent black and white film plus piano player (or for the very lucky, plus orchestra) most were used to in 1908.

Since we don't have a YouTube video of this performance, which I suspect even today, with all our sophisticated expectations of people transcending genre and melding a variety of media, would be a lot of fun to attend, we will have to use our imaginations. We'll have to picture ourselves sitting in one of the beautiful, highly gilded opera halls that dotted up in the oddest places in America, from South Dakota and Kansas to the northernmost reaches of Maine, while the handsome man in the white suit introduced us with his smooth voice and salesman's skill to the Scarecrow, and the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion, as the orchestra played. He would offer his hand to each of the characters, standing immobile in a reproduction of one of the lush color illustrations of his work, and they would step off the page to meet us and talk and sing with each other on stage. (We might already know some of these songs from player pianos or sheet music from previous popular productions of the Oz stories.) Watching them interact with the meticulously tinted film of their adventures – and this might well be the first time we ever saw a film in color – we would probably have a few questions in our minds about the man in the white suit: was he a wizard or a humbug, like the character we would all already have known very well?

Some critics have said that Baum's only motivation in creating the Fairy Logue and Radio Plays was to sell more books. But after reading his books (and I have read almost every one of them), and knowing the man just a little through his biographies, I can't quite accept that answer, although I believe he would be an eager and expert participant in our Facebook-influenced "everyone has a brand" current culture. His love of the American heartland, his fascination with new technology, his delight in astonishing and thrilling his audiences, can lead us to a different conclusion: he was a pioneering interstitial artist, with a strong streak of American showman and salesman, who buoyantly led the way for the many artists, interstitial and otherwise, who were inspired by his work, his ideas, and his moxie.

About the Author

Deborah Atherton is a librettist, fiction writer, and arts administrator, with a lifelong passion for fantasy, science fiction, opera, jazz, and art that falls between the cracks. A graduate of Yale University, her work for music theater and opera has been presented by Lincoln Center Serious Fun, Opera Theater of St. Louis, CAP21, the Woman Becoming Festival of the Culture Project, Parabola Arts, the Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theater at Symphony Space, and National Public Radio. She received a commission for her first opera, Under the Double Moon, written with Anthony Davis, from Opera Theater of St. Louis and for her second, Mary Shelley, written with Allan Jaffe, from Parabola Arts. Under the Double Moon was published in book form by Opera Theater of St. Louis and G. Schirmer. She is currently working on a new music theater piece, Songs of the City, about the difficulties of finding love in New York, with Allan Jaffe.