Moved Permanently

The document has moved here.

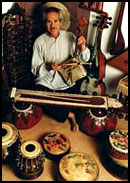

I first encountered Willy Schwarz as a voice on the telephone, announcing himself in Hindi as the friend of a friend. A few days later we met for the first time, and I was bowled over, astonished, and delighted. Almost a decade later, I'm still knocked out by the man and by his musical spirit. It's not just that Willy's a passionate and sublimely gifted musician; there are plenty of great players around. Neither is it that he knows musical styles from all over; there are plenty of pan–global musical epicures around, too.

What amazes me about Willy Schwarz is the meta–cultural tightrope act he carries out every day with such ease and grace. I've never met anyone so completely at home in so many different places. Name a country; it's a pretty good bet that Willy knows, not just a song or two, but a solid evening's worth of performable repertoire. He'll know the old traditional songs and the new variations on them, and he'll sing them with impeccable pronunciation, heartfelt emotion, and a real and pervasive joy; the world's music is a continuous wellspring of delight for this multi–instrumentalist, vocalist, songwriter and composer.

Over the years we've worked together, I've come to appreciate his artistry even more. Willy's original music builds from his intimate connection with the singers he's sung with and the songs he's absorbed from them. He knows the music so well because he knows the people so well, and he knows the people so well (aw, hell, it's one of those chicken–egg things!) because he knows their music so well. When telling the story of an Eastern European expatriate, he can frame it with asymmetrically idiomatic rhythms and the lonely wail of a Bulgarian flute; when speaking with the voice of a Mexican immigrant stuck in a crappy dishwashing job, he does it in authentic corrida style. And perhaps most importantly, when the first–person voice of one of his songs is that of Willy Schwarz himself, the music is that of a genuine world–traveler, a wandering spirit who moves freely from idiom to idiom with the same unconscious virtuosity a great pianist brings to movement from key to key.

It's always seemed to me that "interstitiality" depends overwhelmingly on where the boundary lines are: you can't get between things if you don't know where the divisions are. But Willy's perspective is a different one, based on his lifelong experience of the practical necessities of a working musician. I enjoyed posing questions during our long email conversation; I suspect you'll have as much fun as I did.

Senders: Tell us, Mr. Schwarz: is a "musical idiom" definable at all? If so, how is it defined, and has your operational definition changed over the years you have been making and studying music? Do you think your understanding of "idiom" is different from that of other musicians or listeners? Can you give some anecdotes or examples that will help us grasp the crux of the biscuit?

Schwarz: I always thought idioms are for idiots.

Why? Because they're full of idiosyncrasies! Musical idioms serve only in the broadest or narrowest of contexts. If we're talking about "LUTE MUSIC", then it's understood by a distinct segment of a distinct population that we're concerned with the repertoire and praxis of the pear-shaped string instrument which dominated Europe from the 15th through the 17th century. However, the Chinese p'ip'a, the Senegalese halam, and the Tadjik dutar are all pear–shaped string instruments as well. But few of the above mentioned societal segment will ever have heard of them — or care about them.

What to do with quixotic terms such as 'Rock' or 'Jazz', not to mention absurdities such as 'World Music'? It seems to me that by its very nature, music and music–making resist and defy categorization. The hardest question to answer for me has always been "Oh, you're a musician … What kind of music do you play?" I usually answer somewhat flippantly, trying NOT to sound arrogant; "How much time do you have?" or I sally forth into my own idiosyncratic idiomatic idiocy.

Referring again to the paradigm of lute music: While the enthusiasts may not know or care about the p'ip'a or the halam, they can fill your ears with jabber about the pandora, the vihuela or the theorbo — all relatives of what THEY mean by a 'lute', and all European. They may even know that what's commonly referred to as a mandoline was at one time called a 'treble lute', with its own repertory corpus quite distinct from Bill Monroe or Neapolitan Tarantellas, and that the vihuela was the direct precursor of the modern guitar, which of course is strummed everywhere from Ouagadougou to Borneo.

Perhaps here we come to what you call the 'crux of the biscuit'. Most avid players and listeners of lute music would consider themselves, at least broadly speaking, as within the fold of 'Classical Music'. There's a long list of lutenist/composers from every major court in Europe who produced a large body of works which were published in an established and distinct form of lute tablature, as well as a lute music circuit (call it a network) in the Renaissance (another fuzzy nomenclature, but let's not go there). From Elizabeth's court in England a lutenist/composer named John Cooper traveled to Italy to check out the new styles evolving there, and came back to England, having changed his name to Giovanni Coperario!

More importantly to our discussion, while the lute died the ignominious death of all fads within the royal courts, it was what was happening out on the STREETS which assured its survival in the form of mandolines, fado guitars, hurdy–gurdies, etc. To the not–so–discriminating (or fad–prone) folks out there, it was simply a means to an end — an accompanying instrument for dancing and singing; exactly what it had been in the courts, before it was eclipsed by that newfangled gadget (which the common folks couldn't afford, tune, or carry around with them) — the keyboard. Meanwhile, the p'ip'a, halam, and dutar continued to be loved and played in their respective countries of origin up to the present, when they are being eclipsed by — guess what — the KEYBOARD! (and electric guitars, which ARE affordable, tuneable, and portable.)

Behind all these considerations lie the inherent contradictions of defining musical idioms: European versus non–European, aristocratic versus commoners, 'Classical' versus 'Folk', 'Ancient' versus 'Current', enduring versus fad. There doesn't seem to be, nor has there ever been, a precise way of defining music. Therefore I say idioms are for idiots.

Senders: If idioms are for idiots, are you saying that the vast majority of the world's musicians, who stay inside the styles they know and love, are somehow deprived? That they're idiots? Or is the glib euphony of your axiom masking some kind of deeper truth?

Schwarz: Deprived? Because they lack an analytical overview of their art in a broader context? I don't think so. They're MUSICIANS! They want to know what time's the gig, and how much does it pay? They've chosen their profession, and in this sense they well might be idiots, given that this is an occupation with a traditionally low social status, subject to the whims/exploitation of employers, a lot of time away from home, vagaries of economic conditions, no insurance, etc.etc.

What they gain is first and foremost the opportunity to create sounds which take them and hopefully their listener(s) beyond their normal waking consciousness, into an abstract dimension no amount of words can adequately describe. When they perform, they are practicing a form of shamanism, a form of trance which their subjects enter willingly. Secondly, they've chosen INDEPENDENCE, a necessary concomitant to that creative license.

As for "staying inside the styles they know and love"; I know a group of Gypsy musicians who were hired to perform recently for an evening of Balkan music. It being near Oscar time, they launched into an extended medley of great movie themes! In this sense, they were conforming to the old Roma musical praxis of pleasing the crowd, whether the wealthy socialites of 19th. century Vienna, or the village dances of the Carpathians. Music, because it is aural, cannot be pinned down within neat little, mutually–exclusive territories or styles. Add to this the factor of global media saturation, and I'm sure you'll find that today few Mbuti Pygmies haven't heard Madonna! This ubiquity of musical reproduction, of music–as–commodity, has in less than 100 years completely altered the very nature of music as an art form, which of course presents a plethora of unresolved issues and questions.

I mentioned the traditionally low status of musicians in most societies. This has somewhat changed as a direct result of the media explosion, of what we know as 'the music industry', which, like the car industry or — dare I say it — the government industry, relies on investors, promoters, producers, packagers, publicists, handlers, agents, and managers in order to produce 'a hit'. Success, which admittedly can transcend one's social status, comes literally with a high price tag, especially to that treasured independence and artistic license. Nonetheless, there seems to be no shortage of idiots who are willing to travel that road.

Senders: Can you tell us some stories, Mr. Schwarz … stories that help us understand how you came to be who you are and how you came to make the kind(s) of music you make?

Schwarz: Music has always been for me the supreme social lubricant. As a little kid, it was a way of pleasing my parents and family, as when I'd accompany our little living room pageants, or play the piano for my mom as she trudged through her most hated task–ironing. Coming up in the 1950's, we used to sit around the television, as families previously had around the radio. My father would sometimes turn off the sound (if he didn't like the music) and ask me to substitute at the piano nearby. Of course, I filled in the advertisements, etc. with musical puns, and provided a 'live' soundtrack to whatever we happened to be watching together. This type of musical accompaniment would much later serve me in creating music for theater!

As a teenage performer, I found the ability to widen both the circle of 'fans' as well as my repertoire, my music providing the instant emotional gratification for me as well as the listeners. Of course my parents loved hearing our trio perform the Italian and German folksongs THEY grew up with, but I was also voraciously listening to everything I could find from all over the planet, just trying to acquaint myself with the miraculous and multifarious musics humans make.

I did my first 'field work' at 15, sitting for hours with my Wollensak tape recorder at the humble home of Isaac and Ruby Lester, in Baldwin, Michigan. These black 'immigrants' from Mississippi sang blues, ballads, spirituals, and play–party songs, some of which became staples of my own performing repertory. Their version of 'The Titanic' is, according to one scholar, unique among the many existing variants.

I once went through a major zoo playing a pennywhistle, just to see which animals were visibly reacting to the sounds. After a disappointing response from the exotic birds, the tigers, and even the apes, I came to the huge pit where the 200 year old tortoises from Madagaskar lived. Both of them immediately started crawling toward me from the far end of the pit, and didn't stop until they got to my side, leaning upright against the wall, heads cocked directly at my flute as I toodled on.

Having done my homework as a teen, learning songs from many lands, I found music to be more efficacious than a passport and more precious than money once I started traveling. Stranded in subzero temperatures in Sivas, Turkey, my ability to sing an old 'Ashuq' song from that area resulted in a sumptuous warm meal, a mechanic who fixed the vehicle, and a sendoff with toasts of 'Rakhi'.

Whether sitting up with the prince of Afghanistan all night playing Hindustani classical music, or sharing a song from Malawi to pass the time with an equally bored African in line at the post office, or sitting in a temple singing devotional songs with people whose speech is to me unintelligible, or lustily singing 'Raghupati' with Pete Seeger, coincidentally also waiting for his luggage at the airport in Charlotte; I've always found music to be the deepest form of interpersonal communication, and that the ability to sing even one song in THEIR milieu provides a direct and instantaneous link to the throbbing heart of any culture.

Author's Notes

For further information on Willy Schwarz and a chance to listen to some music samples, visit his homepage. For information on purchasing his CDs, or to listen to additional music samples of Willy's work visit cdRoots, Music From the Road Less Traveled.

Warren Senders has been a musician, teacher and musical thinker since shortly after he became conscious of being anything at all. A vocalist, composer, bassist, percussionist, instrument–maker and general sonic irritant, he is a specialist in the "khyal" style of Indian classical singing. He has performed traditional and original music on multiple continents, and taught music in more contexts and situations than he can remember; for more details see www.warrensenders.com.