It wasn't until I remembered my two encounters with the prostitutes of Havana that I understood the nature of fukú in Junot Díaz's The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

My first encounter happened just a few days into the trip I took to Cuba – legally, through an educational exchange program sponsored in part by Willamette University in January of 1997. Most of the other students thought going to Cuba would be like going to Cancún, only more anarchic and drug-friendly. I was one of the few on the trip with any familial ties to Cuba, and by far I spoke the best Spanish outside of the instructors – and of anyone there the most idiomatic. So I was the expert, the insider: practically a native.

Cue the hubristic comeuppance: the first night we were in Havana, we went to a bar that accepted only American dollars. They were safer for tourists, armed guards keeping out the impoverished locals. But they did let in jineteras. That's what Cubans call prostitutes (the word literally means "jockeys"). They wore terrycloth tube tops about the size of stretched-out sweatbands, skirts so short they were more phenomenological than ontological, and, clearly, no delay-making underwear. Most went barefoot.

Our conspicuously Caucasian group sat together in the bar drinking mojitos, excited to be in a safe bit of danger. It didn't take me long to separate from them. I didn't need to cower with the herd. Cońo, I was Cuban! I bought a Cohiba and stood against the back wall to smoke it, enjoying the magic show that was being performed. It centered around a hole-ridden blanket the magician complained was all he could afford during the Periodo Especiál. But his skills were solid. That's the Cuban way: make up for crappy material conditions with ingenuity and showmanship. The holes actually improved the act, because you could see through them and try to keep an eye on whatever the magician was covering.

It wasn't long before I was accosted. She was late 40s, early 50s. She had tied her small afro into a haystack, wore a brown tube-top, brown short-shorts, and plastic flip-flops that would fade into nothing in a few days, like slivers of soap. She rested a leg against mine and said, "Buy me a cigar."

"I'm not interested," I said, leaning off of her. I looked over to my table. Everyone was laughing.

"Why not?" she asked. "Don't you think I'm pretty?"

"I have a girlfriend."

"That's over there. Here you need a Cuban girlfriend."

I faced her then. How to handle this? I wanted to be definitive but gentle. This was the Periodo Especiál, the worst period of poverty Cuba has ever known. She was working as a prostitute because there were so few ways for women to make money. She was a victim of patriarchal society and late capitalism and several other terms I had learned in graduate school.

With perfect sincerity, I said to her, "I am in love. And a real man doesn't cheat."

She rolled her eyes so hard I could hear it. "żAre you kidding me? żWhat man turns down a pretty woman? At least give me a dollar."

I did. Then I went back to cower with the rest of the Americans.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao is almost my biography. Between the novel's principal male leads, Oscar and Yunior, a portrait of Carlos as a young man emerges.

Plot: there's this Dominican guy named Oscar Wao. That's not his real name; Yunior, along with some other Dominicans, trying to mock him, try to compare him to "that fat homo Oscar Wilde" (180), but with the accent the closest pronunciation they can come up with is "Oscar Wao." Oscar is morbidly obese, and he is obsessed with anime and role-playing games and pretty much every other geek hobby. He wants to be a Dominican genre writer; at one point he asks Yunior what is "more sci-fi than Santo Domingo? What more fantasy than the Antilles?" (6). More fundamentally, he wants love. Alas, all of the features listed above make him more or less date-proof: his weight, pompous vocabulary, exaggerated politeness, and penchant for using the plots of comic books as pick-up lines all but guarantee his virginity. So, will Oscar finally find true love? Spoilers next paragraph!

He does, by novel's end. Of course, he's killed for it, one more victim of Trujillo's poisonous legacy. More on that later.

Oscar's quest for love forms the main plot, but several other members of Oscar's family tree regularly take possession of the narrative, creating a fractured, multivoiced narrative. But that is only the first of a legion of literary devices that serve to create what I would argue is the most heteroglossic text since Ezra Pound's Cantos. To be honest, I'm not sure how most readers can get through the novel. As far as I can tell, the ideal reader for Oscar Wao is someone well-read in literary classics (not just English and American, but Caribbean and South American as well); who has manically consumed genre fiction from childhood on, making a point to reread everything Tolkien has ever written every five years or so; who has more than a passing familiarity with the New World dictators of the Spanish-speaking world, with an especial focus on the Failed Cattle Thief (Trujillo); who knows a great deal of Spanish, the more the better, and the more Dominican the better; and who has an encyclopedic knowledge of American popular culture from at least the 1950s to now, including but not limited to comic books, movies, video games, television, RPGs, and anime.

Okay, so quick quiz: what is the name of Trujillo's villainous sister? Ever see Zardoz? What does it mean when a man calls himself a sucio? Calls a woman a cuero? Who is Gorilla Grodd? If you've just taken 187 hit points of damage, how are you feeling? What is a toto? And please don't say Dorothy's dog.

I wasn't 100%. Cuban and Dominican slang-words are plenty different; Cuban and Dominican histories run parallel but are, of course, distinct; and I just flat out didn't get every geek reference. But I know enough to know that, in the inaugural hardcover edition of Oscar Wao, Gorilla Grodd was misspelled. Díaz wrote it with only one "d," and none of his editors was nerd enough to catch it. But I was.

I grew up rolling D&D dice and playing Atari and watching way too much television. I cleared out the sci-fi and fantasy collections of every library my mother would drive me to. I, too, wanted to be the Latino Tolkien, or as an acceptable consolation prize, the Latino Gary Gygax. I was Oscar.

Except I wasn't morbidly obese: I was pretty fit, pretty sporty in fact. And I had girlfriends – not many, but maybe just enough to avoid an Oscar-like persecution. But those exceptions aside, I can't describe to you how uncanny and unsettling it was for me to read Oscar Wao. Oscar is a Latino otaku with whom I share an almost exact nerd trajectory. It was impossible not to relate to him.

And yet, impossible not to relate to Yunior, the novel's hypermasculine narrator, as much as I would like to distance myself from his all-too-familiar bullshit swaggar. Yunior's voice for me is the perfect admixture of feral charm and infuriating, relentless sexism – perfect in the sense that anything less would be less authentic. By turns Yunior is clever, bitter, scholarly, self-satirizing, and self-aggrandizing. He is locked into the same machista mindset that has crippled generations of men, of every culture, time, ethnicity – that a man is a simple animal, and all the learning and sophistication he may gain in life is mere filigree, frosting atop a crude macho core. Yunior can press 340 pounds, writes stories that celebrate drugs and gunplay, and is pathologically preoccupied with using women for sex. He cannot stop himself from enacting that same stultifying myth of manhood we can render in a single Spanish-cum-English word: machismo.

But that is Yunior the character. There is also Yunior the writer. Within the fiction of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Yunior writes The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. He does so to perform what he calls a zafa, a cleansing word or ritual that with luck will break the fukú, the curse that has followed the de Leon family and all who suffered from the post-Trujillo Dominican diaspora.

Specifically, that fukú comes directly from Trujillo when the dictator tries to have his way with Oscar's Aunt Jacqueline and is parried by Oscar's grandfather Abelard. Yunior says of Trujillo that he is the Dominican Republic's "Number One Bellaco in the Country. Believed that all the toto in the DR was, literally, his. It's a well-documented fact that in Trujillo's DR if you were of a certain class and you put your cute daughter anywhere near El Jefe, within the week she'd be mammando his ripio like an old pro and there would be nothing you could do about it!" (sic, 217). In other words, for Dominicans of that time (and for the generations after haunted by him), Trujillo is the absolute embodiment, the greatest earthly avatar, of machismo. "If you think the average Dominican guy's bad, Trujillo was five thousand times worse," says Yunior (217). It is that machismo which leads directly to the generations-long fukú that ravages the entire island nation for decades, and stretches its influence even into the United States to claim more victims. The fukú is machismo.

The fukú is machismo. It took me a long time to realize that. For a long time I was ineffably enamored of the novel. I knew I loved it, but, when faced with criticism – as I was one day by one of my colleagues, an expert in Latino literature, who found Yunior's voice merely sexist, infuriatingly self-assured and macho – I found myself at a loss to say why. I hadn't yet worked through the deep irony of the novel. It was on the surface as broken and postmodern as a Ph.D. in English could want, a fractured collection of incomplete narratives, with almost all the characters consumed by the merciless Angel of History; it was stuffed to bursting with references to geek culture that I reveled in seeing in a "legitimate work of literary fiction"; it was funny the way much Latino humor is funny, fast and black and fearless and savage. But what I loved most about it, inarticulately at first, is that it identifies machismo as a soul-crushing fukú for both women and men. Machismo is a curse that must be broken.

And it takes an Oscar – a geek, a failed man – to ultimately break it. In the last pages of the novel, after we know Oscar has been killed by the henchmen of the jealous former boyfriend of his novia Ybón, Yunior breaks the abyssal sorrow at novel's end by letting us know that Oscar did not die a virgin, but indeed had relations a few days before being murdered.

Phew!

But it's not intercourse that breaks the fukú. It's how anticlimactic Oscar finds intercourse to be.

... what really got him was not the bam bam bam of sex – it was the little intimacies that he'd never in his whole life anticipated, like combing her hair or getting her underwear off a line or watching her walk naked to the bathroom or the way she would suddenly sit on his lap and put her face into his neck. The intimacies like listening to her tell him about being a little girl and him telling her that he'd been a virgin all his life. He wrote that he couldn't believe he'd had to wait for this so goddamn long. (Ybón was the one who suggested calling the wait something else. Yeah, like what? Maybe, she said, you could call it life.) (335)

It's Oscar's ability at the end to see past sex as a conquest and instead engage in an act of communion with his beloved that sets aside all of the machista nonsense that has been relentlessly described as the desire of all men throughout the novel. Communion allows Oscar to find what Ybón defines as life: it is a brief life, but it is wondrous in a way those stunted by machismo can never know. And as Yunior recounts this last lesson, you can almost hear him learning. There is a kind of reverence to the way Yunior surrenders the last words of the narrative to Oscar, after all: "The beauty! The beauty!" (335). You can almost hope that, besides all that he has already gained by writing this book, this last posthumous push from Oscar will help Yunior finally free himself from the fukú that has cursed every previous generation of men, and that continues to haunt us today: all of us, of both genders and virtually every society. But to do that, we're going to need a lot more zafas. A lot more men like Oscar.

One night, two weeks into my trip to Havana, a group of us Americans danced on the Malecón with a group of prostitutes. We were six Americans, three male, three female. The jineteras were girls and women, mid-teens to mid-twenties, and they out-numbered us at least by two to one. They weren't working, but celebrating a birthday of one of their own. I, idiot, did not realize they were jineteras until I was told. By them. Proudly.

One of the American women collected five dollars from each of us and turned a nearby rum stand into an open bar for all of us. The owner, elated by the windfall, took out a small radio and played salsa. It became a game to try and teach the American boys how to dance. The three of us were hopeless, but luckily we were drunk. Each guy was in turned dragged to the center of the ad hoc dance floor to make a fool of himself.

I was paired with a woman who wore a white terrycloth dress that, like an accordion being squeezed, was falling down and rising up simultaneously, threatening to leave everything but her stomach naked. She treated me like her own personal stripper pole. She danced in front me, or sidled up next to me, or pressed herself against me like a tango dancer, her body erect, one of her legs wrapped around me, a hand caressing my cheek. Several times I tried to scamper away, but was, between the pushing crowd and my indefatigable partner, dragged back to the center until the song was over.

While the next guy was being humiliated, my dance partner, standing next to me in the circle, asked me if I was gay. She used a much-less-polite Cuban word.

I said I wasn't. Then she said, "I didn't think so. You're a terrible dancer, and everyone knows [homophobic Cuban word for homosexuals] know how to dance."

I made some noncommittal noise, tried to pretend that I was terribly interested in the plight of the new stripper pole. But she kept going. "I don't get you. Your Spanish is good. You sound like a real Cuban. You have dollars like a tourist, so it's not the money. We've been together for almost half an hour, and you haven't propositioned me yet."

"You're not working tonight," I said.

"Of course I am," she said.

Okay then. "I have a girlfriend. Back home."

She nodded, watched the dancing for a little bit. Then she said, "I don't think I'd like America."

"Why not?"

"The men aren't macho enough."

It's one of the nicest things anyone's ever said to me.

Work Cited

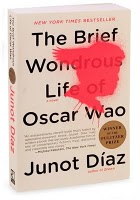

Díaz, Junot. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. New York: Riverhead, 2007. Print.

About the Author

Carlos Hernandez is currently serving as the Deputy Chair of the Department of English at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY. He earned his Ph.D. in English with an emphasis in Creative Writing from Binghamton University in 2000, and is the author of over 20 works of fiction, a novella, the story "The Assimilated Cuban's Guide to Quantum Santeria" in Interfictions 2, and the coauthor of Abecedarium, an experimental novel published by Chiasmus Media in 2007. Look for new short stories from Carlos in the upcoming anthologies You Don't Have a Clue: Latino Mystery Stories for Teens (Arte Público) and Bewere the Night (Prime Books).