| |

|

Coloring Between the Lines |

|

|

| |

| by Gregory Frost |

| |

(This is loosely based on a talk given to the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society. The original, decidedly different in some details, was interrupted at various points for interstitial intrusions by the Bonzo Dog Doo–Dah Band. I've checked with the doctors and they say that everyone who was in the audience is expected to make a complete recovery.)

I'm going to talk to you tonight about a breaking down of barriers, walls, definitions within our fantasy genres and beyond. This spins off an article I recently wrote for the New York Review of Science Fiction.

|

| |

I. Crayons and Order

As children, many of us here in the U.S. were given coloring books and taught to color inside the lines. This creates nice, orderly compartments of blue and red, and even Blue–Violet and Violet–Blue, which really were different colors even though they had the same components. It made parents proud to watch our motor skills develop from mad jagged slashes of color to orderly, inside–the–line work. It also helped them discern that the thing we'd drawn was in fact a cat, which let them off the hook when presented with our latest work of genius. It also programmed us to think in terms of neatly assembled parts. This helped us later when we assembled plastic models and jigsaw puzzles and had to fit pegs into holes to prove our aptitude for peg–fitting. You can probably see where I'm going here. The tendency to compartmentalize is a far–reaching one. Librarians use the Dewey Decimal System to maintain order, to fit literature into appropriate categories, to keep chaos from being the dominant theme in our libraries; and God knows, we who use those libraries to research would never want it any other way. Give me order; give me anal–retentives in charge of my library. However, don't put them in charge of what I choose to read (and I hope Mr. Ashcroft and his thugs are listening, not that it'll do me any good).

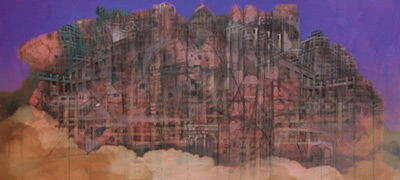

I would like for you to think of literature as a huge house. In it there are lots of rooms. One room is the Modern Room. It's full of Ernest Hemingway novels, and Jack Kerouac, and early John Updike stories about people on commuter trains. Paintings on the wall are abstract, or cubist, with sharp edges, splashes of color.

Down the hall there's another room, called the High Fantasy Room. It's full of books about Celts and dragons and hobbits, King Arthur and Conan. Murals on the wall are by Rowena and Boris.

Still another room, the Western room, has a lot of books in it, but they're all covered in cobwebs now and dusty. The walls here are painted Zane Grey. You can see, looking at the floor, that not too many people have come in here lately, either, but the cushiony furniture suggests that once upon a time they did.

We get cozy with our rooms the way we get comfortable coloring inside the lines in our coloring books. As adults we find we've been trained to see this house in this particular way. "This is SF. This is romance. This is horror."

My first three novels were arguably high fantasy, even though I think I did something more with them than produce cookie–cutter high fantasy novels. That's how they were marketed. Most of my short fiction is dark fantasy or horror. My fourth novel was science fiction and some of the short stories are, too. My story that was on the Hugo and Nebula ballots this year is science fiction. My latest novel, Fitcher's Brides, is a fantasy–horror–romance. So what am I? Into what room of this house do I fit? It's clear I haven't been staying put.

Now there's nothing wrong with staying put. Lots of us have whole careers out of it — in fact if you're looking for a secure career with a devoted following, that's probably the best way to go. Throw down your sleeping bags in the middle of one of the rooms and take up residence there. If this weren't true, there wouldn't be identifiable rooms in this house in the first place. Furthermore, some people who take up residence in one room become very uncomfortable when asked to move to another room — when a publisher, say, requests that they go work in another room for awhile because the air in this one is getting stale. These folks have gotten so comfortable there. Their readers know to look for them there. What will happen if they moved to another room? Will the readers understand and come find them? It's dark and scary out there. Better to stay with what you know, right?

However, more and more of us seem to be rejecting this option — enough that some have begun to notice us, not as individuals — not as the multi–beasted manticores we are — but as part of a larger phenomenon.

Market forces may push us: Other genres, notably romance, are marrying and producing bastard children with science fiction and fantasy and supernatural stories. As with any phenomenon like this, you can try and pin it down. You can say that this has been going on for maybe a decade. But in fact this has been going on for much more than a decade. Richard Matheson was doing it in the '50s, but that seems not to have been noteworthy; or maybe we've become more protective of our rooms, our genres, over time. We're afraid the walls might collapse now.

However, fearful or not, you can't stop movements from arising. Especially when they come at you from some other room, catching you unaware.

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

next page

|

|